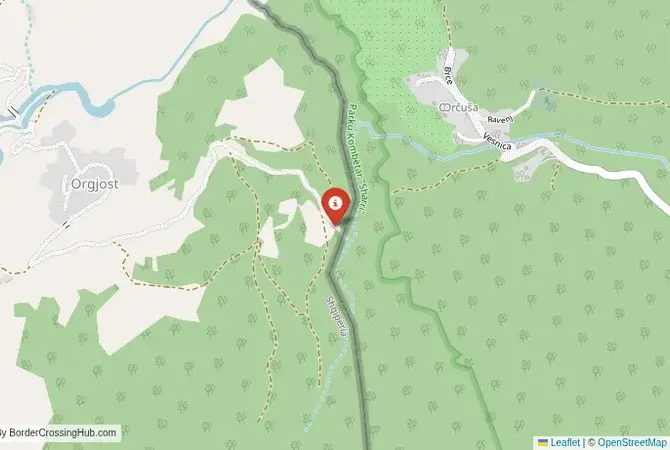

Approximate Border Location

Wait Times

15–60 min pedestrians

Just crossed? Tap to report:

Operating Hours

06:00 AM–10:00 PM

Crossing Types

Pedestrians only

Border Type

Land crossing via road

Peak Times

07–10 AM mornings

Daily Crossings

300–700 crossings

Currency Exchange

Limited nearby (ALL, EUR)

Safety Information

Remote, low risk

Languages Spoken

Albanian/Kosovar

Accessibility Features

Ramps, limited assistance

About Orgjost & Orqushë (pedestrian)

Monthly Update (February 2026):

Footpaths lead into the Orgjost & Orqushë Border Crossing, where silence often comes before movement. In February 2026 it’s been mostly stable, with pedestrians clearing quickly when the post is open. Vehicle traffic isn’t a factor here. Weather and staffing patterns are what shape access.

A Closed, Remote Crossing in the Land of the Gorani

Important Note for Travelers: This border crossing is a simplified, local checkpoint that is currently closed and not operational for international travel. This guide is provided for historical and informational purposes only. The border crossing that once connected the Albanian village of Orgjost with Orqushë in Kosovo was a journey into one of the most remote, inaccessible, and culturally distinct corners of the Balkan Peninsula. This was not an international checkpoint in the modern sense, with paved roads and formal buildings, but a “simplified crossing point” intended only for the local residents of the immediate border villages. It was a simple footbridge or a basic path, a way for people to cross the border to visit family, attend festivals, or work on their ancestral lands without making an arduous journey of many hours to the nearest official checkpoint. It represents the most basic and fundamental form of a border crossing: a recognized point of passage for a local community, a concession by the state to the realities of life in a divided land.

Operational Details

This checkpoint connected Albania’s Kukës County with the Dragash Municipality of Kosovo, right in the heart of the Shar Mountains. Its operation was extremely limited, a reflection of its purely local function. It was typically open only on certain days of the week, for a few hours each day, often corresponding with local market days or holidays. It was strictly for pedestrians who were permanent residents of the designated border communes, a list of villages agreed upon by both states. No vehicles were allowed, and it was not open to tourists or citizens from other parts of the country. Its purpose was purely to facilitate local cross-border life, a pragmatic solution to the challenges of a border drawn through a sparsely populated, high-altitude mountainous region where traditional life depends on movement across the valleys.

A History of the Divided Gora Region

The history of this region is the history of the Gorani people, a unique South Slavic ethnic group who are predominantly Muslim and have inhabited the Shar Mountains for centuries. They speak their own South Slavic dialect (Nashi) and have a unique culture that blends Slavic, Islamic, and pre-Slavic Balkan traditions. The modern border, established in the early 20th century and solidified after World War II, divided the Gora region, the Gorani homeland, between Albania and Kosovo (then part of Yugoslavia), with a small part also falling within North Macedonia. The villages of Orgjost in Albania and Orqushë in Kosovo are part of this Gorani homeland. The simplified crossing point was a vital link for this community, allowing them to maintain the family, social, and cultural connections that had been severely strained by the political division. It was a way to mitigate the harsh reality of a line that had cut through their ancestral lands.

Former Border Procedure

The border crossing procedure, when it was operational, was a very simple and personal affair, a world away from the impersonal and often intimidating experience at a major international post. Local residents, who were on an approved list and carried special local identity documents or permits, could approach the checkpoint during its limited opening hours. They would present their documents to the Albanian and Kosovar border police stationed in small, simple huts at either end of the crossing. The checks were focused on confirming identity and residency. It was a process based on community recognition rather than anonymous international travel protocols, where the border guards often knew the residents by name. It was a border crossing built on trust and local necessity.

The Surrounding Region: The Shar Mountains

The surrounding area is a beautiful, wild, and mountainous landscape. On both the Albanian and Kosovar sides, the region is characterized by high-altitude pastures (`bačije`), where shepherds graze their flocks in the summer, traditional stone villages, and a way of life that has changed little for centuries. This is one of the most remote and least-developed parts of the border. The nearest towns of any significance, like Kukës in Albania or Dragash in Kosovo, are many hours’ drive away on winding mountain roads. The appeal of the region lies in its pristine nature and its authentic, traditional culture. The area is part of the Shar Mountains National Park on the Kosovo side and the Korab-Koritnik Nature Park on the Albanian side, both protecting a rich biodiversity, including bears, wolves, and lynx.

Closure and Legacy

Simplified crossing points like Orgjost-Orqushë have been progressively closed in recent years as both countries work to modernize and secure their borders, often as a prerequisite for closer integration with the European Union. The strict requirements of modern border management, focused on preventing smuggling and illegal migration, have little room for such informal, local arrangements. The emphasis is now on a smaller number of full-fledged international checkpoints with sophisticated surveillance and control systems. The ongoing political situation in the region also contributes to the tightening of border controls. The path is now likely overgrown, and the border is secured against any unauthorized passage, a hard reality for the local Gorani community.

Final Considerations

The Orgjost–Orqushë border crossing is a ghost of a more informal and localized approach to border management. Its story is a fascinating glimpse into a time when special arrangements could be made to serve the needs of local communities living on a frontier, a recognition that borders are not just lines on a map but have a profound human impact. Its closure was an inevitable consequence of the modern emphasis on border security and the standardization of international protocols. It remains a poignant reminder of the human element of borders, of the simple need for a farmer to cross a mountain to reach his pasture, or for a cousin to visit family in the next valley, even if that valley is in another country. It is a lost connection in a land that has known many divisions.

No reviews yet.